Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is an eye disorder caused by abnormal blood vessel growth in the retina, the light-sensitive part of the eyes, of premature infants. Bleeding from these vessels may scar the retina and stress its attachment to the back of the eye, causing partial or complete retinal detachment and potential blindness. ROP can cause permanent vision problems or blindness, and it is estimated that large numbers of preterm infants worldwide become blind or visually impaired because of ROP every year.

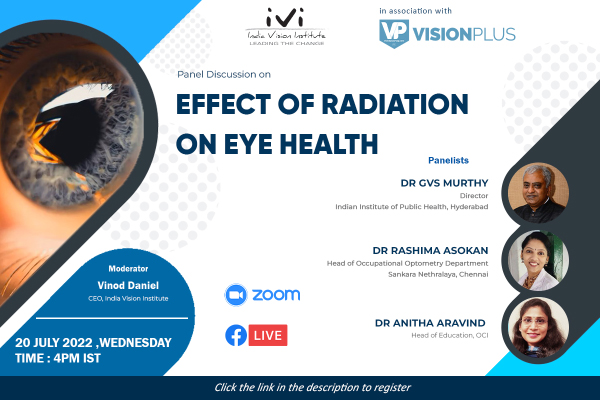

India Vision Institute (IVI) and VisionPlus Magazine commemorated World Prematurity Day, on 17 November, hosting a panel discussion ‘Retinopathy of Prematurity: A Concern of Vision Impairment and Blindness in Preterm Infants.’ Moderated by Vinod Daniel, the panel at the discussion comprised Dr Vasumathy Vedantham, Medical Director, Vitreoretinal Surgeon, Paediatric Retina Specialist, Radhatri Nethralaya, Dr Shruti Nishanth, Strabismologist, Paediatric Ophthalmologist and Neuro-ophthalmologist, M.N. Eye Hospital, and Sailaja Manda, Research Fellow, Schepens Eye Research Institute.

The world is going through what is often described as ‘the third epidemic of ROP’, where a majority of cases are from middle and lower middle-income countries. A large number of preterm infants in the South Asia and Asia-Pacific region have been affected. Over 40% of the world’s premature infants are born in India, China, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Indonesia.

Vinod Daniel drew the panel’s attention to the fact that many preterm infants in India and the South Asia region risk developing severe ROP. It is estimated that Asia accounts for half of the world’s birth and ROP-related blindness. Premature babies are born before their retina develops fully. When this development happens outside of the mother’s womb, it can result in ROP. The infant’s retina, forfeited of blood supply, starts detaching. If left untreated, the child may become permanently blind.

Vinod Daniel drew the panel’s attention to the fact that many preterm infants in India and the South Asia region risk developing severe ROP. It is estimated that Asia accounts for half of the world’s birth and ROP-related blindness. Premature babies are born before their retina develops fully. When this development happens outside of the mother’s womb, it can result in ROP. The infant’s retina, forfeited of blood supply, starts detaching. If left untreated, the child may become permanently blind.

Diagnosing ROP is a challenging and demanding task that requires training and professional expertise. Mr Daniel pointed to a “shortage of trained eye care practitioners in the country” capable of diagnosing ROP, especially in remote rural areas. He asked the panelists whether there is a “reasonable short-term solution for places where there are not enough trained eye care practitioners.” According to Dr Vasumathy Vendantham, it is very difficult for a primary eye care practitioner, or sometimes even a general ophthalmologist, to identify ROP. A practitioner needs to be specifically trained to diagnose the condition. “Since we do not have a sufficient number of suitably trained ophthalmologists in India, we need to train paramedical professionals such as optometrists and the technicians to diagnose ROP,” she noted.

Employing the services of optometrists to screen for structural eye defects and identifying babies who will need specialised ROP screening is a plausible solution to the skills-deficit problem. Complex cases identified at this primary stage can be referred to opthalmologists experienced in pediatric ophthalmology.

Optometrists and technicians can be trained in the use of the hand-held fundus camera to image an infant’s eyes. For treatment, portable lasers that can be transported to remote locations can also be of considerable help. The effects of ROP can be long-lasting, and for this reason, it is important that ophthalmologists communicate well with practitioners working at the grassroots level in remote areas, and with the parents and families of children. Parents and families ought to be made aware of the hurdles and opportunities that await their children after treatment. “Optometrists and Ophthalmologists need to play a role in holistic management of ROP by helping parents and the children achieve the most productive outcomes,” observed Sailaja Manda. After treatment for ROP, even if a child has to go to a blind school, it does not necessarily mean the end of the world. With functional visual skills training, a child can be trained to use their vision for various activities of daily living.

Even if a child’s vision has been severely impaired as a result of ROP, an ophthalmologist or an adequately trained optometrist who has a good understanding of the visual capacity of the child can work with the parents to help them understand the child’s visual capabilities and determine ways to make best use of them. Practitioners can help with training the parents and children on how to make best use of their ROP-affected vision.

Answering Mr Daniel’s question on the integration of ROP screening and treatment into India’s public health system, Dr Shruti Nishanth identified the need to focus on more than just diagnosis. “Neonatal care, as a whole, needs to improve and be geared to challenges posed by preterm births,” she noted. Public-private partnerships in providing eye health solutions, especially in remote areas, can prove beneficial. The public and private sector both have inherent strengths, which if harnessed in unison, will serve as complementary force multipliers.

Governments must also give an impetus to training eye care practitioners to diagnose and treat ROP. Workshops and conferences can, for instance, be held to train government doctors in the identification and management of childhood eye health issues. Equally important is the role of optometrists and technicians, who are crucial in taking ROP diagnosis to the most vulnerable rural population groups in India. Improvements in the training of these eye care professionals will enable them to be more effective in identifying ROP, thereby facilitating treatment. Optometrists could, for instance, be made to undergo internships with Ophthalmologists and use that training to gain experience and knowledge for carrying out ROP screenings.

– Varun Nambiar